|

This is a visible light, whole-sky

image of our galaxy, the Milky Way. This is how we see it, but at

shorter and longer wavelengths it looks quite different.

Here it is in infrared light at a

wavelength of 2µ, as a snake might see it. Infrared light at

this wavelength is radiated mostly by warm dust.

And in radio light at a wavelength of

a few millimeters, you can see the bulge of old stars around the

Galactic center.

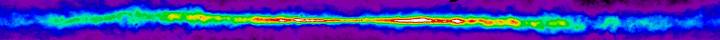

This radio image shows the

distribution of atomic hydrogen in the Milky Way, the material from

which the next generation of stars will form.

Many stars in our Galaxy shine at very short wavelengths, in ultraviolet and

x-ray light, as seen here. Actually, honey bees see the

Milky Way much like this because their eyes are sensitive to

ultraviolet. Some flowers direct bees to pollen and nectar by marking

their petals with landing strips and taxiing directions that reflect

only ultraviolet light which only bees can see. |